A spate of recent heist movies feature armored car robberies for a reason – violent action and high drama – with the villains taking big risks for a huge payout. The filmmakers certainly get it right when it comes to making movies that keep you on the edge of your seat. However, the CIT industry loathes Hollywood’s depiction of armored vehicle attacks and bank robberies. In reality, lives and property are put at risk and there usually are no happy endings.

Use of Force: Armored Cars v. Banks

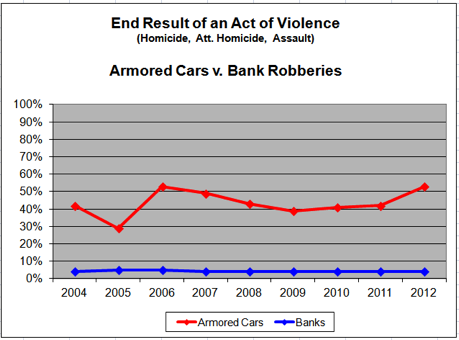

Robbery statistics reviewed over the last ten years clearly show that armored car robberies are extremely violent when compared to bank robberies. Although vastly more common, in traditional bank robberies an act of violence occurs on average 4% of the time, a figure that has remained relatively flat over the last decade. Comparably, from 2004 to 2012, per the chart (below), an annual average of 43% of armored car robberies involve a violent act as the final outcome.

In many traditional bank robberies, the threat of a weapon, or the passing of a note suggesting there is one, typically forces a bank teller into immediate compliance. That same tactic doesn’t have the same effect on armored car personnel.

By their very nature, nearly 90% of armored car robberies are perpetrated through the use of or threat of violent force as described above. A few incidents involving snatch-and-grab do occur annually, but the vast amount of incidents involve, at a minimum, the display of a weapon by the suspects to coerce the armored car personnel to comply with their demands. Previously, over half of the armored car robberies occurring each year merely involved the display of a weapon by the suspects to accomplish their goal.

But, the end result of violent force is where we should really take note. For the purpose of analysis, an “act of violence” ranges from physical assault and battery, including the use of chemical sprays, to punching or striking with an object such as a gun, to attempted homicide through the discharge of firearms by suspects, and unfortunately, escalating all the way to the murder of armored car personnel.

Escalation of Violence

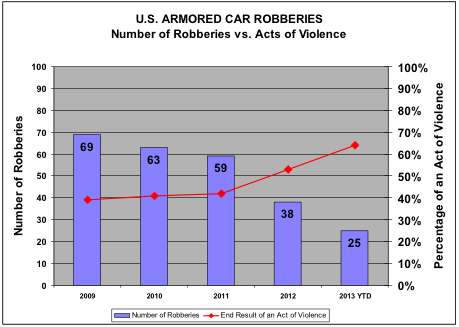

An alarming recent trend in armored car robbery incidents has emerged from 2009 to present. Despite a steady decrease in the overall number of robberies, the rate of violence used in the commission of those robberies has increased dramatically. Throughout 2012 and continuing into 2013, over 50% of robberies resulted in an act of violence. The violence is clearly escalating.

An increasing amount of incidents now begin with the perpetrators skipping any attempt at a verbal command, instead choosing to, “come in shooting,” or opening fire as their means of making their initial demand.

The phenomenon of violence increasing as robberies become fewer is not a unique occurrence within the cash-in-transit world by any means. In fact, this condition has been observed on the national scale in recent years.

According to a study conducted by economists Brendan O’Flaherty and Rajiv Sethi, from the period of 1993 to 2005, the number of robberies dropped from 6 robberies per 1000 population to 2.6 per 1000. However, during this same time period, there was a notable increase in the proportion of robberies resulting in victim injury.

Among the factors contributing to the disparity between fewer robberies and increased violence that were explored in the study were the concepts of deterrence and victim hardening. Nowhere are these ideas more prevalent than in traditional cash-in-transit and armored transport operations.

Deterrence

When analyzing crime, deterrence refers to the policies that make crime less attractive to all types of potential criminals by increasing the expected punishment that follows the commission of a crime. Armored car robberies qualify for adjudication under the Hobbs Act, in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 1951. This law considers armored car robberies to be a direct interference with commerce, equating them with Federal crimes such as bank robbery.

As a Federal offense, armored car robberies prosecuted under the Hobbs Act carry stiff penalties for the offenders. In theory, this should serve to reduce the overall number of offenders committing robberies, but, in actuality, it has the unavoidable effect of leaving only the most violent offenders that are willing to take the high risk.

Improved affiliations between law enforcement agencies and the cash-in-transit industry certainly help bridge the gap between the initial crime and the end result of conviction. Fostering working relationships with federal and local police, not only during and after an investigation, but also before a robbery ever happens will always pay off.

Victim Hardening

It should go without saying that armored cars and the crews operating them are hard targets and are the primary factors contributing to the need for increased violence by suspects. Criminals looking to attack an armored car on the street know that they need to bring a significant amount of force to accomplish their illicit goals.

The physical obstacles are clearly in place. The average armored car body and glass are designed to withstand fire from even magnum power-factor small arms calibers. Attacking a crew of two or three armored car personnel is also a considerable risk, as they are likely wearing bullet resistant vests, and are guaranteed to have firearms of their own, with the know-how and training to respond with deadly force.

The aggressive street operations, security procedures, and monitoring programs instituted by many of the major U.S. armored car carriers in recent years also contribute to the hardening of armored crews. Programs like unannounced street surveillances enable security managers to assess specific weaknesses in individual team members, and help to sharpen crew skills such as observation and presenting an alert image. Periodic physical site surveys of customer locations help to spot location vulnerabilities, allowing the armored carriers to adjust service tactics and procedures, or enhance crew compliments where needed.

Combating Increased Violence

These factors of deterrence and victim hardening in the armored industry are likely very significant in reducing the overall number of attacks on armored carriers. The side effect of having fewer robberies, however, appears to mirror the national trend of attracting the most violent offenders to the high risk crime of an armored car takedown. In weeding out the offenders that are not willing to risk serious incarceration time or even their lives, those who remain are brazen, violent, organized, and willing to use deadly force from the onset.

Combating these types of criminals might seem insurmountable, but an industry effort to stay the course with the already proven effective measures must continue. This should include:

• Information sharing on an industry-wide level about developing crime trends and new robbery tactics used in armored car robberies.

• Adaptability and flexibility in armored car street operations and service tactics.

• Enhancing unannounced random street inspections and customer site risk surveys.

• Continued education and training of armored car personnel, with a specific focus on robbery response.

• Increasing the vigilance of armored crews on the street, while at the same time combating complacency in areas not experiencing armored car robberies.

• Fostering relationships with law enforcement to include establishing points of contact.

• Educating members of law enforcement about armored car operations through programs hosted by carriers, including informing them about the necessity for special security procedures used in the armored industry.

• Requesting that marked police units periodically trail armored cars operating in their patrol areas to show a visible presence.

Sources:

• The National Armored Car Association (NACA).

• The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Bank Crime Statistics (BCS), 2004-2011.

• Brendan O’Flaherty, Columbia University, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Department of Economics & Rajiv Sethi, Barnard College, Columbia University, Santa Fe Institute; “Why Have Robberies Become Less Frequent But More Violent?” October 2009; The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, Vol. 25, Issue 2, pp. 518-534, 2009.

Author: Joseph Labrozzi